Bleeding heavily from cervical cancer, 48-year-old Lebohang Pitso was rushed to Queen Mamohato Hospital in Lesotho in May. "It was like a heavy cover was removed from my face," she said after receiving a life-saving blood transfusion. Her survival was made possible by the country's voluntary blood donors and a national blood service working behind the scenes. Her story is a powerful reminder that investing in safe, reliable blood systems isn't optional—it's a matter of life and death.

As global health budgets tighten and U.S. federal support for essential programs recedes, national blood transfusion services in low- or middle-income countries (LMICs) are facing dire consequences. The recent stop-work order on U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) projects has disrupted critical operations in countries such as Kenya—where the Ministry of Health has warned of a collapse in blood services unless more than 2.7 billion Kenyan shillings ($20.9 million) are urgently mobilized. In Liberia and Malawi, governments are scrambling to fill the void, but domestic budgets are already stretched thin.

These cuts reflect a broader trend for national blood transfusion services. Over the last decade, major donors—such as the U.S. President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the Global Fund have gradually pulled back support for blood services, historically tied to HIV services and have done so with limited transition planning or increased commitments from domestic resources.

Now, U.S. cuts to family planning programs, traditionally a major driver of reductions in maternal mortality, threaten to compound the crisis. More unintended pregnancies in underresourced settings will increase the risk of complications, such as postpartum hemorrhage—one of the leading causes of maternal death globally and a condition for which timely access to safe blood is often the only life-saving intervention.

The burden of noncommunicable diseases such as cancer continues to rise, requiring robust transfusion services

The burden of noncommunicable diseases such as cancer continues to rise, requiring robust transfusion services. Global momentum around maternal health—including the World Health Organization's (WHO's) postpartum hemorrhage roadmap—has underscored the importance of blood access. A quarter of postpartum hemorrhage deaths globally are attributable to a lack of safe blood, up to approximately 50,000 preventable deaths occurring primarily in sub-Saharan Africa. Treatment for severe malaria, a condition that affects nearly half a million children under the age of 15 annually there, also requires safe blood.

Yet national blood transfusion services remain chronically underfunded, misunderstood, and institutionally marginalized. Without adequate access to safe blood, even the most ambitious maternal and child health strategies will fall short.

Amid substantial reductions in U.S. support for global health, access to safe blood risks once again falling through the cracks. Promising new initiatives focused on women's health, such as the Prysm Initiative, which mobilizes high-net-worth individuals for reproductive health, and the $500 million Beginnings Fund, backed by the Gates Foundation and the Children's Investment Fund Foundation, offer hope that fresh funding could alleviate some financial constraints. But if these and similar efforts overlook safe blood, they will undermine their goals.

Weak Systems and Low Donor Prioritization

LMIC demand for safe blood has not been met for two reasons: too few voluntary blood donations and weak national blood systems to screen, process, and distribute blood and blood products. In LMICs, donation levels average one-third the volume of higher income countries. These shortages disproportionately harm the most vulnerable communities—women, children, and lower socioeconomic status families—contributing to significant, preventable excess mortality and derailing global progress toward the UN Sustainable Development Goals.

A lack of prioritization drives this gap given that safe blood is often neglected by global health donors' funding streams. Although access to safe blood shapes outcomes across health systems, it is largely excluded from issue-specific global health strategies [PDF]. Even when access to safe blood is recognized as an essential HIV treatment, such as to prevent infection through blood transfusion, it is deprioritized in favor of competing needs. This trend is evidenced by the sharp decline in the already limited support for national blood transfusion services in many sub-Saharan countries.

The lack of funding has also forced national blood transfusion services to scale back necessary functions such as training health workers in safe transfusion practices. Similarly, funds to combat malaria are directed toward the purchase of bed nets, rapid diagnostic tests, and artemisinin-based combination therapies with no support to the national blood system. Although the WHO classifies blood as a drug, its supply chain differs from other medicines and the procurement processes are not well understood by global health advocates. The confusion surrounding the safe-blood supply chain makes it difficult for donors to identify solutions to access.

Plastic bags filled with donated blood are stored in a cooler at a donation center, in Nairobi, Kenya, on January 9, 2012. REUTERS/Noor Khamis

In recent years, safe-blood access has garnered more international attention. The WHO launched the Action Plan for Blood 2020–2023, and government leaders and civil society organizations have advocated for strengthening the safe-blood supply chain through discussions facilitated by USAID, the Clinton Health Access Initiative, the Postpartum Hemorrhage Summit, and the Align MNCH conference in 2023.

Progress

To raise attention and support for safe blood, USAID partnered with the WHO, Results for Development, Boston Consulting Group, and Nigeria-based Health Strategy and Delivery Foundation to support national blood system leaders in Liberia, Malawi, and Rwanda. From 2021 through 2024, this program identified challenges leaders face in prioritizing and executing high-impact interventions and galvanized support across disparate health programs within the national health system writ large. The program resulted in more than a dozen new publications and global resources for national blood system leaders, including a Blood System Self-Assessment Tool released through the WHO as a framework for evaluating a country's safe-blood ecosystem and dismantling barriers to increase access.

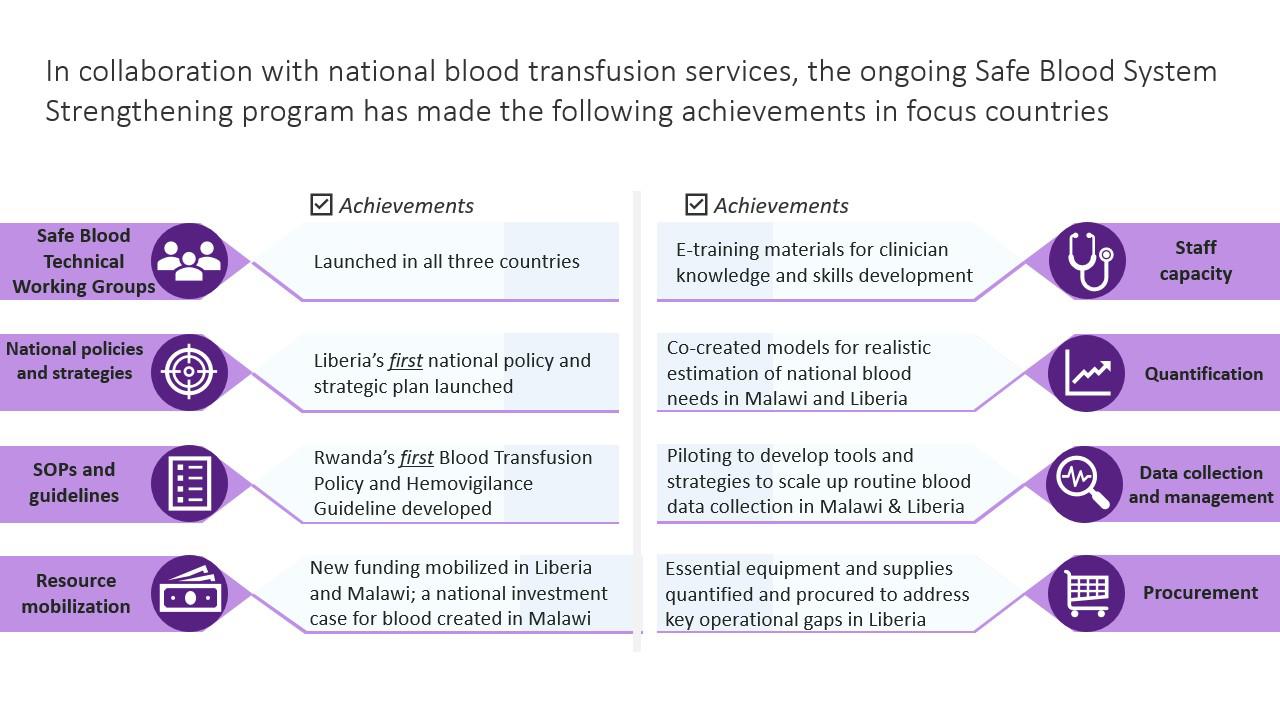

The program also drove meaningful change across the three countries: e-learning for pre- and in-service training on transfusion medicine for health workers in Rwanda, a national blood system policy and strategy in Liberia, mobilization of new domestic and donor resources in Malawi and Liberia respectively, quantification of national blood needs and national blood transfusion services, and supplies to inform national blood transfusion services planning and operations in Malawi and Liberia. The following figure provides a snapshot of the program's milestones in strengthening national blood systems in three countries.

Key milestones to strengthen national safe-blood systems in Liberia, Malawi, and Rwanda Figure courtesy of R4D

The program showed that blood system leaders in LMICs need not only technical support but also operational and advocacy support to write convincing proposals, articulate compelling investment cases, and amplify stories of why access to safe blood matters. As some of the smallest units within health systems—often at arms-length from core ministries of health as special programs or parastatal organizations—national blood transfusion services benefit from peer learning and exchange of templates and approaches that can bolster their work.

Moving Forward

History shows that progress in global health for vulnerable populations comes only through sustained advocacy and support for national leadership. This pattern has been crucial in the fight against malaria, HIV, tuberculosis, and neglected tropical diseases—and in expanding reproductive health access for women. Over the past decade, health system strengthening and universal health coverage have reemerged as priorities—encompassing building blocks like financing and workforce—with dedicated organizations now championing these areas.

Advocates for safe-blood access can and should learn from these efforts. Global health now has a chance to build on the momentum, tools, and partnerships created through the USAID program. Funders and partners should invest in a safe-blood access catalyst platform that would focus on three objectives: empowering blood system leaders across LMICs to drive improvements and mobilize resources, promoting adoption of proven tools and strategies to amplify the needs of and strengthen blood systems, and identifying and unlocking opportunities for sustainable blood system funding through national, regional, and global channels.

Now is the time to foster alliances with adjacent sectors—surgery, maternal and child health, malaria, and NCDs—that are also directly affected by inadequate blood access. A focused, coordinated investment in leadership—paired with operational and advocacy support—can transform national blood systems. By making safe-blood access a sustained priority, health leaders and funders can strengthen the broader health system writ large. It's time to elevate safe blood as a global health priority—and act with the urgency it deserves.

Young Malawians leave a clinic after donating blood in Malawi's commercial center, in Blantyre, Malawi, on June 14, 2005. REUTERS/ Eldson Chagara

Lyudmila Nepomnyashchiy served as deputy director at the Center for Innovation and Impact within the U.S. Agency for International Development's Global Health Bureau.

Thomas Muyombo serves as the manager of the Blood Transfusion Division at the Rwanda Biomedical Center.

Bridon M’baya is medical director of the Malawi Blood Transfusion Service.

Onyekachi C. Subah is the director of Liberia’s National Blood Safety Program.

Adeel Ishtiaq is a program director at Results for Development.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·