On a quiet Monday afternoon in May, a man stood in a busy courtroom in the Ramsey County Courthouse. He was there to see Tim Carey, presiding judge for the county’s Mental Health Treatment Court, a specialized court designed to offer alternative options for people with severe and persistent mental illness (SPMI) like schizoaffective disorder, schizophrenia or bipolar disorder facing criminal charges.

Ramsey County Mental Health Treatment Court, which, along with the county’s DWI Court, celebrated its 20th anniversary this spring, takes a holistic, treatment-centered approach to its work with participants, helping them access a range of agencies, including mental health and addiction treatment and housing and employment supports. The court’s overarching goal is to break the seemingly unending cycle of involvement with law enforcement and the legal system that often plagues people with untreated SPMI.

For the man standing in front of Judge Carey and the assembled group of court workers, this was a big day. He had spent nearly two years taking part in the court, a voluntary process that can keep participants who follow the judge’s orders out of incarceration and on the path to recovery from mental illness and addiction.

This afternoon, he would graduate and move on to the next step in his life.

Carey looked down from his bench. The man in front of him shifted slightly, but looked back at the judge with a calm, if shy, gaze.

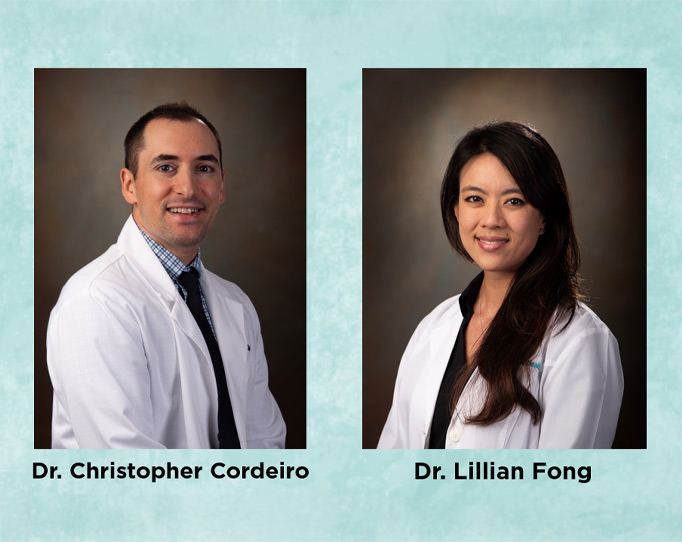

Anthony McCartney graduates from Ramsey County Treatment Court during the 20th Anniversary celebration in April. Credit: Courtesy of Minnesota Judicial Branch

Anthony McCartney graduates from Ramsey County Treatment Court during the 20th Anniversary celebration in April. Credit: Courtesy of Minnesota Judicial Branch“You chop wood and gather water,” Carey said to the participant, referring to the Buddhist belief in the importance of finding enlightenment through focusing on everyday tasks. “Your success today is based on your commitment.”

There were a few more words of praise from the judge, and from other court officials before the participant had a moment to speak about his own experience, which included weekly appearances in court over the first several months, time in a residential treatment facility, submitting regular urine tests, and meetings with a probation officer and a mental health case manager. The process, the man said, “helped me to be accountable for my actions,” he paused and added, “I want to thank the team.”

In the end, the man received a certificate and had his photo taken with the judge. There was a round of applause, sweets set out on a table to mark the moment, and then it was the next participant’s turn.

Carey glanced at his notes, looked the next man in the eye, and said, kindly, “It looks like you made all the UAs (urine tests). That’s a big achievement. Good work.” Then he and his team began to ask questions about the man’s search for work and his experience in a residential addiction treatment program.

It was time to move on to the next case.

‘It’s a revolving door’

Ramsey County’s Mental Health and DWI Treatment Courts were created in 2005 as a collaboration between the courts and the St. Paul City Attorney’s office to handle gross misdemeanor offenses committed by people struggling with addiction and mental illness. Eventually, the programs grew to include the Ramsey County Attorney’s Office and felony-level charges. In the two decades since the courts’ founding, 673 people have participated in their programs in lieu of going through the traditional legal process.

A central goal of Mental Health Treatment Court is to set people sometimes referred to by law enforcement or social service professionals as “familiar faces” — or individuals with SPMI who, for multiple reasons, tend to cycle in and out of incarceration, addiction treatment and homelessness — on a different life course.

Allison Husman, Mental Health Court case manager, said that sometimes the law enforcement professionals who work with this population start to see them as faceless, hopeless statistics. In Mental Health Court, she said, they try to look at participants with unjaded eyes.

“Everyone knows that mental health and addiction are common themes among people involved in the criminal justice system. If you can’t intervene on those aspects for people, it’s a revolving door. Even if they go to jail or prison and are forced into sobriety and get on mental health medication, when they get out they often relapse or stop taking their meds and those issues crop right back up.”

Husman said that she and her colleagues view Mental Health Court as an opportunity for second chances.

“In a program like this, we try to stop that cycle, and in the short time participants are with us, we focus on how we can get them connected to programming,” she said. “We tell people their time in this court lasts 18 months to two years. People feel like that’s a long time, but it actually is a really short period of time to accomplish so much.”

To outside eyes, Mental Health Court may seem like a gentler alternative to the traditional judicial process, but the truth is the commitment required to graduate the program is serious, Carey said. He and his colleagues expect full participation in the court. It takes focus, commitment and time to complete the process. Participants, he said, “have to come in every week until they meet several milestones, submit gallons of urine samples. They have to go to treatment, have to regularly talk to court staff.”

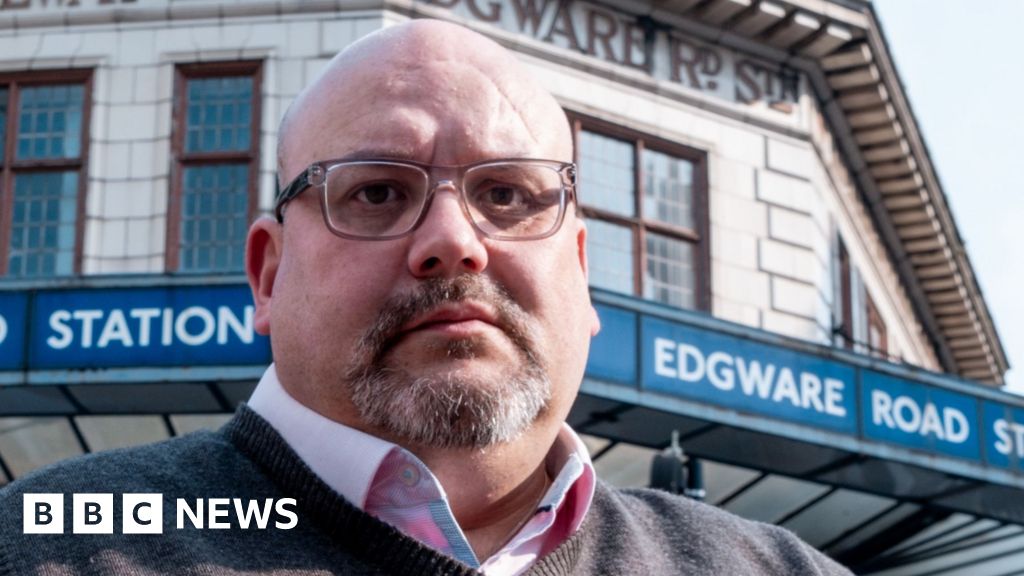

Tim Carey, presiding judge, Ramsey County Mental Health Treatment Court. Credit: Courtesy of Minnesota Judicial Branch

Tim Carey, presiding judge, Ramsey County Mental Health Treatment Court. Credit: Courtesy of Minnesota Judicial BranchRonnell Nadeau, Ramsey County Mental Health Court probation officer, explained that the court is highly organized and regulated by design. Because staff take participants’ recovery goals seriously, participants are expected to take their own goals seriously, too.

“Once you plead in, you are given these conditions you are expected to comply with for your mental health going forward in this realm,” Nadeau said. “There is more structure here than there is in regular court. This helps people take accountability for their behavior and the trauma and the struggles that they are going through.”

Courtroom staff — including social workers, attorneys, probation officers and even the judge — are there to offer support and guidance, Nadeau said. This can be the key to turning over a new leaf: “There is a team of people that support you and give you access to the providers and the things you need to recover. If you are willing to go along with the program’s requirements, you are going to get the stability you need to maintain a stable life.”

Ideally, as their time with the court progresses, participants gain support and insight that helps improve their prospects for recovery and success in the outside world, Carey said. During their time taking part in Mental Health Court, participants are, he explained, “in addiction and mental health treatment. They are trying to get jobs. They are dealing with housing support.”

All the appointments and meetings required for these programs makes participants’ regular appearances in Mental Health Court valuable to their continued recovery. “We give a lot of praise,” Carey said.

Not everyone graduates from Mental Health Court. Sometimes, participants just can’t — or won’t — meet the court’s expectations, Nadeau said.

“Sometimes you’re like, ‘OK. What more can we do?’ We do get to the point where we’ve offered multiple treatment options, we’ve suggested mental health services. It doesn’t seem that the person wants to do this. We get to the point where we say, ‘I’m sorry but we’ve exhausted all possible alternatives to help you.’ It takes a lot to get to that point.”

Though the court’s graduations can feel full of hope and promise, Nadeau said that she and her colleagues are realistic enough to know that not all dreams for the future stick. Sometimes the pull of addiction or unwanted side effects of medications can drag graduates back into old habits or behaviors. Still, there continues to be heartening stories from the court — graduates who have worked their way through the program and have managed to create a new, more hopeful life for themselves and their families.

Nadeau recalls a young participant she met early on in her work with Mental Health Court.

“She wasn’t doing well at all,” she said of the participant. After a month of participation, court staff found the woman a space in the residential treatment program RS Eden. She lived there for several months, until it was time to move onto the next step. “She has two young boys,” Nadeau said. “She needed to get into housing post-treatment, and thankfully I knew of a women’s shelter program.” The participant and her children moved into the shelter two days later.

“In the last six months, she’s been doing so well,” Nadeau said. “She’s been chemically free since November. She just got approved for housing through Wilder. She and the boys are going into their own apartment.” For the participant, this is a huge accomplishment, Nadeau said, and for court workers, the participant’s recovery feels like a victory: “It gives me goosebumps.” Today the participant is enrolled in college, she said.

‘I get to show that I care’

For many of the team members, being part of Mental Health Treatment Court has been an opportunity to do work that aligns with their beliefs. Before Husman joined the court 11 years ago, she worked for a short time as a police officer. She thought that working in law enforcement could be a way to help the community, but she soon grew frustrated with the limitations of the job.

“My very brief stint in law enforcement opened my eyes to a lot of things,” Husman said. “When you are working with people in law enforcement, there are a lot of issues that you can’t get involved in that lead to people getting involved with the criminal justice system over and over again.”

Looking for what felt like a more effective way to help, Husman decided to earn a master’s degree in social work. “I asked myself,” she recalled, “‘How can I actually have the time to delve into the things that are making people’s lives so difficult?’ I wanted to work with people in an ongoing way, to help really solve their problems. Social work was a way to get there.”

For several years, Nadeau worked at Dorothy Day Center in St. Paul, helping people with SPMI and addiction find housing. “That was a very stressful job,” she said. “Every day we did not know what we were coming upon.” She said she kept seeing clients, “cycling through treatment, jail and homelessness. While I was there I witnessed a lot of clients dealing with untreated mental health and chemical addiction who continued to spiral with no interventions to help them.”

Nadeau decided to look for work as a probation officer, because she felt the role would give her more latitude to help people find ways to transition out of incarceration.

The role at Ramsey County Mental Health Court, which she has held since October 2024, feels different from the work of a traditional probation officer. “I get to show that I care because it is a supportive program,” Nadeau said. Many of her clients, even though they have been diagnosed with SPMI, have not had much experience working with a therapist: “I am able to talk to them and encourage them, to let them know it is OK to talk to somebody about their trauma.”

Before he went to law school, Carey worked with sex offenders as a Ramsey County probation officer. Later, he earned a law degree, and took a job as an assistant Ramsey County attorney. This work sparked his interest in helping people who struggle in their day-to-day lives because of mental illness and addiction.

“I’ve always been interested in mental health issues and people’s well-being,” he said. “It’s part of what I grew up with. I believe there are a lot of people who struggle, and you should be compassionate to them. Someday you could be the one requiring compassion.” He hopes that commitment shines through in his interactions with participants: “Just know we aren’t going to wad you up and throw you away.”

At every graduation, Husman said that she and her colleagues all hold dreams for participants’ futures — but they are also realistic about the odds for their continued recovery.

“I hate to say it, but just because they are successful on graduation day doesn’t mean they are going to be successful in six months or even a couple of years down the road.” To stay motivated, Husman said court workers are, “focused on, ‘What does it look like for this person today? Are they better than they were when they came to us?’ The bar isn’t set the same for everybody. If a person comes to us with zero resources, if they leave with even a couple of things, that would be a success.”

And there are Mental Health Treatment Court graduates whose success has exceeded expectations, Husman added: “I have heard back from a few clients after graduation who tell us they are doing phenomenally well, so much better than they were when they came to us. That’s the dream.”

English (US) ·

English (US) ·