A member of the Mongolian Red Cross visits with a local herding family that received various forms of emergency assistance after a period of extreme cold caused widespread damage to livestock across the country in 2024.

A member of the Mongolian Red Cross visits with a local herding family that received various forms of emergency assistance after a period of extreme cold caused widespread damage to livestock across the country in 2024.In Mongolia, where extreme winter cold spells, known as “Dzud”, are becoming more frequent due to climate change, these can spell death to people and animals.

But in recent years, herders in remote regions can get up-to-date advance warnings of pending extremes, as well as detailed advice prompting them, for instance, to stock up on food and water supplies, thanks to a unique collaboration between the International Red Cross and Red Crescent and the Mongolia national meteorological service.

The story was showcased at a recent Geneva event launching a big expansion in a collaboration between the World Health Organization and the World Meteorological Organization, which aims to better harness climate and weather information to protect people’s health.

The initiative, supported by $11.5 million in new investments from the Rockefeller Foundation and Wellcome Trust, aims to foster more effective linkage between national meteorological agencies and ministries of health in at least 80 low and middle-income countries in Africa, Latin America and Asia.

The collaboration will also include seven prototype projects to demonstrate how national met services can more effectively harness cutting-edge climate and weather science for public health purposes.

This represents a significant scale-up in the activities of the WHO-WMO Climate and Health Joint Programme, founded in 2018 to accelerate the uptake of climate and weather science by public health policymakers and practitioners.

Reimagining the global health mission

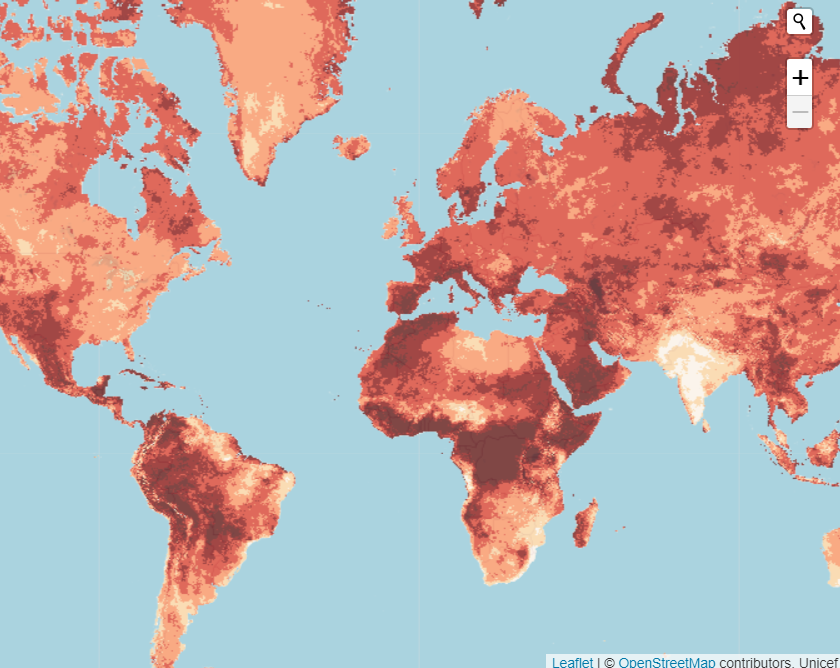

Frequency of heatwave events in the 2020s. Most of the world now sees 6-9 events (medium brown), or 9-15 or more events (dark brown) a year.

Frequency of heatwave events in the 2020s. Most of the world now sees 6-9 events (medium brown), or 9-15 or more events (dark brown) a year.Extreme heat kills an estimated half a million people a year and resulted in $835 billion in potential lost income in 2023 alone, according to the latest data.

“After a ‘decade of deadly heat,’ it is clear that public health’s status quo is not going to cut it,” said Naveen Rao, senior vice president of health at The Rockefeller Foundation at a side event of the World Health Assembly in May.

Naveen Rao, senior vice president of health, The Rockefeller Foundation.

Naveen Rao, senior vice president of health, The Rockefeller Foundation.“To save and improve the lives of the world’s most vulnerable people, we have to reimagine how we meet our mission today and invest in novel solutions both providers and patients need today.”

Global temperatures are expected to remain at record levels for the next five years, according to WMO’s latest report, published on 29 May.

Even so, only half of the world’s national meteorological services issue extreme heat warnings. And only 23% of national health authorities currently use climate and meteorological data in their health planning, WMO deputy director general Ko Barrett told the WHA side event.

Advancing heat-warning systems in 57 countries alone could save nearly 100,000 lives per year, according to a recent WHO assessment.

Health is one of the best entry points for climate discussion

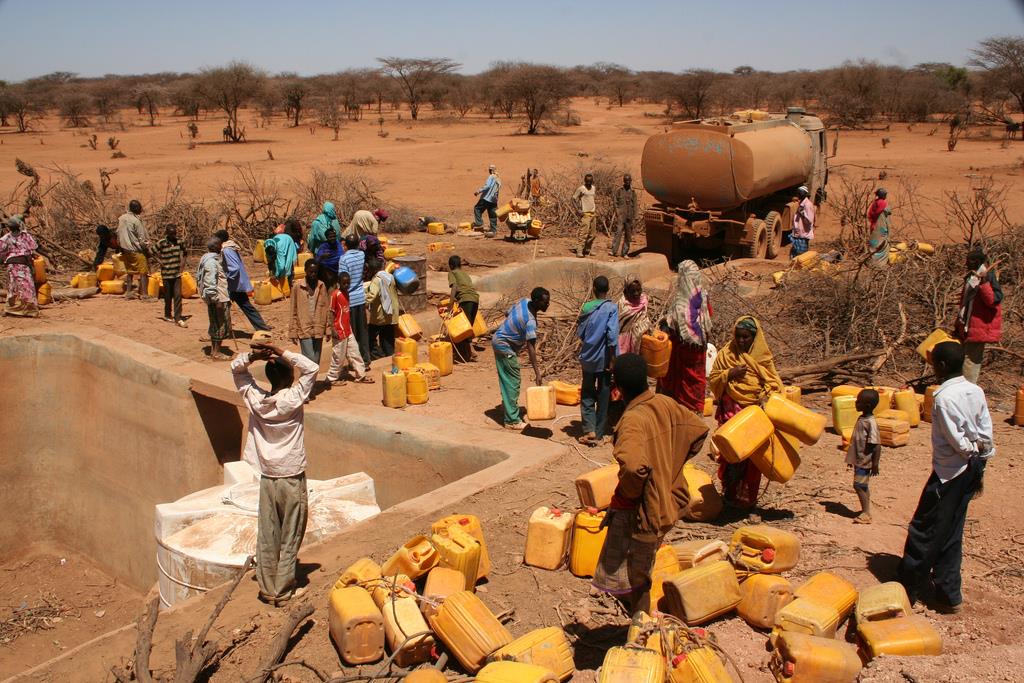

Water shortage in Ethiopia. Population exposure to heat is increasing due to climate change, with multiple knock-on health impacts.

Water shortage in Ethiopia. Population exposure to heat is increasing due to climate change, with multiple knock-on health impacts.Scientific recognition of the links between climate change and health impacts dates back decades. Already 35 years ago, the WHO was becoming active in UN climate fora.

But including meteorological information into the equation is a more recent innovation, says Joy Shumake Guillemot, WHO-WMO Joint Programme lead. The aim, she says, is to turn “climate intelligence into health intelligence” to make health systems and services more climate-ready.

“Health is one of the best entry points to talk about climate and climate impacts because people care about their health,” said Dr. Anna Stewart Ibarra, executive director of the Inter-American Institute for Global Change Research at the WHA side event, dubbed: “Temperatures Rising: Preparing and Protecting for Extreme Heat.”

“We can talk about systemic issues like no potable water, urban development, climate change, loss of biodiversity, but health is sort of this very clear entry point,” she said. “They [politicians and the public] care about their own health, their children’s health, and their communities’ health.

In a fireside chat, Professor Celeste Saulo, Secretary-General of the WMO, and Dr Jeremy Farrar, WHO’s Chief Scientific Officer, highlighted the growing partnership between their two organisations. Both emphasised the urgent need to break down silos between sectors to address increasingly complex global challenges such as outbreaks, extreme heat, food and water insecurity, and most pressing — inequity.

‘Co-production’ of knowledge

“Climate affects everything—from health to transport to energy,” Saulo said. “It’s only through comprehensive, multi-sectoral approaches that we’ll avoid harming one sector while helping another.”

Celeste Saulo, Secretary-General of the WMO (left) with WHO’s Jeremy Farrar, incoming ADG for Health Promotion, Disease Prevention and Control.

Celeste Saulo, Secretary-General of the WMO (left) with WHO’s Jeremy Farrar, incoming ADG for Health Promotion, Disease Prevention and Control.While the WMO and the national meteorological services that they work with generally make their data widely available, health ministries often under-use it due to communication gaps and a lack of knowledge about how to interpret and use this intelligence for decision-making, Saulo pointed out.

The disconnect between health, climate and meteorological communities exists in both emerging and developed economies, said Prof. Francisco J. Doblas-Reyes, who leads the Department of Earth Sciences at the Barcelona Supercomputing Centre (BSC).

Francisco J. Doblas-Reyes, who leads the Department of Earth Sciences at the Barcelona Supercomputing Center (BSC)

Francisco J. Doblas-Reyes, who leads the Department of Earth Sciences at the Barcelona Supercomputing Center (BSC)But affluent countries can more easily bridge those divides harnessing new technology and scientific innovation could help bridge these divides.

So global inequalities will be exacerbated if health and met services in low-and middle income countries can’t access new methods of working and knowledge thus produced—something the WMO-WHO joint initiative aims to address.

“Equity is not granted—we must work for it,” Saulo stressed. “That means truly listening, co-producing solutions, and building systems that include everyone from the start.”

Collaborations on the ground

Herder in Mongolia protects his livestock during a Dzud.

Herder in Mongolia protects his livestock during a Dzud.Despite the gaps, there are many projects and countries where collaborations are happening.

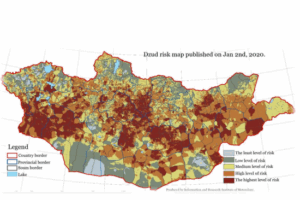

Meghan Bailey described one such example, in which the International Committee of the Red Cross and Red Crescent (ICRC) collaborated with the Mongolia meteorological service to develop early action protocols linked to a Dzud Risk map that not only warn herders of extreme cold weather, but advise them what to do in different scenarios.

Dzud Risk map. Collaborations with the health sector have linked the risks to early action that saves lives and livelihoods.

Dzud Risk map. Collaborations with the health sector have linked the risks to early action that saves lives and livelihoods.That included development of trigger points where, for instance, “the risk level for livestock loss becomes so high that you do that, you do that, you take action. In this case, those actions were veterinary supplies, emergency feeding, and also cash,” said Bailey, who works with the ICRC’s Climate Center.

“The idea was to help herders keep their animals alive so they can stay in their livelihoods—and not have to go through the psychological distress of having large livestock loss and then forced migration.

Such up-to-the minute advice helps build trust that can be critical in getting fast action in other moments of crisis, said Bailey.

“Because you’re actually giving people what they need when they need it. And so it means when you give, you know, other health advice, or you give the next warning that they’re with you,” added Tulip Mazumdar, who moderated the conversation.

Taking a regional approach in the Caribbean

Inter-sectoral meetings at regional level are an important means of bringing the sectors together as well as introducing new ways of working, said Dr David Farrell of the Caribbean Institute for Meteorology and Hydrology, which is based in Bridgetown Barbados.

From left: David Farrell; Ibrahima Sy, Senegal; Agnes Soares da Silva (Brazil); Anban Pillay (South Africa); and Ousmane Ndiaye, African Meteorological Center in a panel discussion with a journalist-moderator.

From left: David Farrell; Ibrahima Sy, Senegal; Agnes Soares da Silva (Brazil); Anban Pillay (South Africa); and Ousmane Ndiaye, African Meteorological Center in a panel discussion with a journalist-moderator.So when the Caribbean Climate Outlook Forum convenes virtually or in person, the invited experts include health specialists along with those from disaster relief, water, energy, agriculture and tourism. “They’re all focused on understanding what the climate impact will be in their part of the Caribbean,” Farrell said.

The Caribbean has already experienced the value of this multi-sectoral approach, he pointed out. For example, meteorologists might forecast heavy rainfall, prompting the agriculture sector to anticipate an abundant harvest, leading a prime minister to consider increased investment in farming.

But if health officials are also at the table, they can warn that the rainfall could trigger disease outbreaks, potentially reducing productivity and nullifying expected profits.

“We have these complex scenarios that we have to work through, and that’s why we bring everyone together, so that everyone can see and converse about what the challenges are that we are facing,” Farrell explained. “How does one challenge link into the other challenge? And so, rather than going with bilaterals between the climate and health sectors, we made it a multilateral arrangement. Everybody signs on the same page. Everybody sees the same information.”

Dr. Agnes Soares da Silva, of Brazil’s Ministry of Health, spoke about the importance of establishing such cross-sector collaborations well before emergencies occur.

She cited the big dengue outbreak that hit Brazil in 2023 and 2024, infecting more than 6.5 million people and resulting in approximately 5,000 deaths.

During that period, health and climate experts began meeting daily in a “situation room,” to anticipate the next level of needs. After the crises ebbed, the meetings continued on a weekly basis. And this year, she notes, dengue cases has so far declined by around 75%, with a similar sharp drop in deaths, a feat she credits, in part, with the links established with climate specialists which helped health officials better target interventions.

AI and ‘digital twins’ will accelerate collaborations

Electric car manufacturers use digital twins technology to update software efficiently.

Electric car manufacturers use digital twins technology to update software efficiently.Technology, including AI, will ultimately play a key role in accelerating collaborations – harnessing the power of more linked-up climate and health intelligence, said Doblas-Reyes.

He called out, in particular, the potential applications of using AI with “digital twins” technologies.

Digital twins are services that integrate data, software, and infrastructure to solve complex problems. For instance, car companies use digital twins technology to upgrade the software that goes into electric vehicles, he said, noting that “electric cars are essentially batteries with an engine and a lot of software.”

So when that software needs to be updated, performance testing is done with digital twins – before being installed in an actual car – and that saves time and money.

“And this is the kind of element that we can bring into the climate and health services sector.”

Already, over the past three years, there has been a revolution in the creation of AI-driven weather modeling systems.

Combining AI and digital twin approaches can accelerate access to high-quality, climate-sensitive health information – without the need for extensive testing in real life.

“Climate services can co-design these digital twins to reduce the time necessary to provide an answer, reduce the barriers and increase the efficiency of health-related warnings and adaptation decisions,” Doblas-Reyes said, adding that despite that potential, “technology alone is not going to save us.”

Elaine Fletcher contributed to this report.

Image Credits: © Rachel Punitha/IFRC, UNICEF, Oxfam East Africa, Maayan Hoffman, Mofali/UN/OCHA , United Nations , Ernest Ojeh/ Unsplash.

Combat the infodemic in health information and support health policy reporting from the global South. Our growing network of journalists in Africa, Asia, Geneva and New York connect the dots between regional realities and the big global debates, with evidence-based, open access news and analysis. To make a personal or organisational contribution click here on PayPal.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·