Climate action is facing strong headwinds at the federal level, but we’re not out of options here at home. Evanston resident Kelly Fidei, who volunteers with Climate Action Evanston, has a suggestion for others who may be sweating in the summer heat: “Explore getting a heat pump.”

That advice may seem counterintuitive, given that they’re called heat pumps. But these amazing devices are essentially reversible air conditioners that transfer heat rather than producing it. In the winter, they extract heat from the outside air and move it inside; and in the summer, they move heat out of the house to cool the air inside.

That was news to Fidei when she first considered getting a heat pump almost four years ago. She’d been living in her Fourth Ward house for 25 years. Her three window air conditioner units kept her cool, but they were noisy and temperamental, they used a lot of electricity, they had to be taken out in the winter and “they had a nasty habit of dripping onto my hardwood floors,” she says.

She was worried about climate change, but as a single mother, she had budget constraints. Her “heat pump epiphany” came on a hot summer day when her brother was visiting. He was blazing through folk songs on his guitar, she says, and they were both sitting there sweating, when he paused and asked, “Have you thought about a heat pump?” He knew how important climate was to her and was surprised she hadn’t considered it. “I didn’t know at the time it could also function as an air conditioner,” she says.

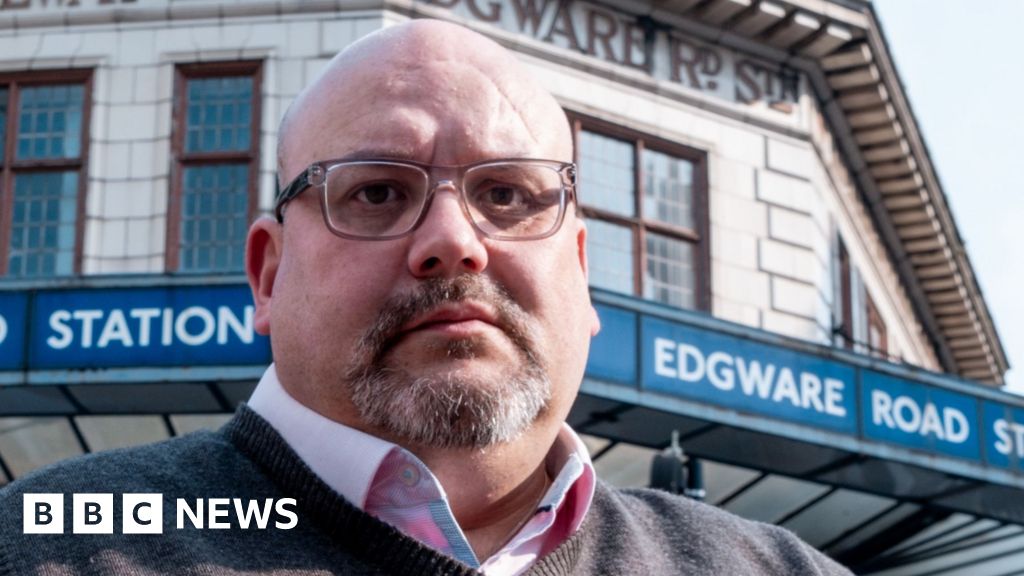

Kelly Fidei points to the smart thermometer that controls both the heat pump and backup furnace. Credit: Wendy Pollock

Kelly Fidei points to the smart thermometer that controls both the heat pump and backup furnace. Credit: Wendy PollockExpanded range

Heat pumps have been in common use in southern states for a while, mostly because they’ve long performed well in mild winters in addition to providing summer cooling. South Carolina has the highest percentage of households with heat pumps (46%) in the United States.

Now that heat pumps have been developed that work even in subzero temperatures, they’re becoming more common in northern states, too. In the first 11 months of 2024, Americans bought 37% more air-source heat pumps than gas furnaces.

Midsummer convenience

Fidei wasn’t thinking about the middle of winter when she started to investigate heat pumps. She just knew she was hot, she wanted to replace her troublesome window AC units, and she wanted to cut carbon emissions. With her brother’s encouragement, she talked to several contractors and eventually ended up working with a local HVAC company called TRG. The house already had air ducts that served her gas furnace. So TRG was able to connect a Bosch air-source unit to the ducts and wire a smart thermometer to manage the seasonal switch from cooling to heating. The gas furnace stayed in place but isn’t needed until temperatures drop into the 20s. The result: comfort during hot weather, and no more window units leaking on the floor or blocking the view.

When she switched out conventional ACs for a heat pump, Fidei was part of a national trend. “Over the past 10 years, heat pumps have raised their market share of residential cooling equipment from 34% to 44%,” RMI reported this summer. (RMI was founded in 1982 as the Rocky Mountain Institute “to improve America’s energy practices.”)

Heat pumps use electricity, just like conventional air conditioners. But according to the Building Decarbonization Coalition, they use, on average, 29% less electricity during periods of peak demand than central AC. Plus, the same appliance also provides heat.

As the climate continues to heat, more people will need air conditioning to survive. According to Atlas Buildings Hub, sales of central AC “have already increased a substantial 15% in the U.S. over the past ten years in comparison to the previous decade, and the trend is likely to accelerate.” That could increase stress on the grid, especially during summer hot spells when demand is highest. Shifting to heat pumps could help reduce that stress.

Options in a greener grid

Fidei continues to use her gas furnace as a backup on the coldest winter days. But by opting for a heat pump, she has been able to achieve her goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Not only does she use less gas in the winter, but by relying more on electricity she takes advantage of the greening of the grid as more solar and wind come online. She emphasizes that there isn’t just one way to go about transitioning to lower-emissions heating and cooling. Her contractor did a good job of educating her about the options, she says. “There are different tiers. You can choose the level that’s right for you.”

“But my heat pump story isn’t just about individual actions,” she writes. “It’s about community building, coming together with a common vision for our future — the future of our planet and our children. Every time I look at my heat pump, I think of my daughter, nieces and nephews, and the world they’ll inherit. I want it to be a world where winters still exist, where forests still stand tall and clean, where we’ve found the courage and smarts to turn the tide on climate change. Together, we can create a ripple effect of change, one home at a time.”

Resources

Climate Action Evanston volunteers are helping people find ways to transition to cleaner, more efficient energy. Look for their Climate Coaches at the Farmers Market and, beginning in September, the Main Library. Subscribe to the CAE newsletter for updates.

Why heat pump sales are heating up, an account of midwinter installation of a hybrid gas furnace and heat pump system, Evanston RoundTable, Feb. 3, 2025.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·