In Philadelphia, the leading causes of death are heart disease, cancer and unintentional drug overdose. While some of these deaths are caused by things out of our control – like genetics – many are largely preventable.

Preventable deaths are the result of a series of decisions. Whether a person decides to smoke, eat lots of fried foods or be a couch potato, their decisions – sometimes unconsciously – can affect their health.

I’m a health communication expert and public health researcher at Temple University in North Philadelphia. I began working in public health in the late 1980s at the beginning of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, and before that I worked in marketing and public relations. I have spent my career thinking about how health decisions are like many of the decisions consumers make each day around which products to buy.

One key difference with health decisions is the inherent risks involved. There isn’t much risk in trying a new brand of cereal, but there is risk in riding a motorcycle without a helmet.

Many people have a “that won’t happen to me” attitude when making a decision that involves risk. This element of “risk perception” has guided my interest in health decisions and how to use commercial marketing techniques – the same ones companies use to sell products – to encourage people to get vaccinated, get a colonoscopy or get treated for a medical condition.

Breaking demographics into psychographics

One strategy I use is segmentation analysis.

Segmentation analysis is the process of looking at groups of people who may look like they are all similar on the surface – such as Black women from North Philadelphia – and then breaking them into smaller groups based on differences in their attitudes, beliefs or behaviors.

Looking at these “psychographics” instead of demographics like age or sex can help public health communication researchers better understand how to communicate effectively.

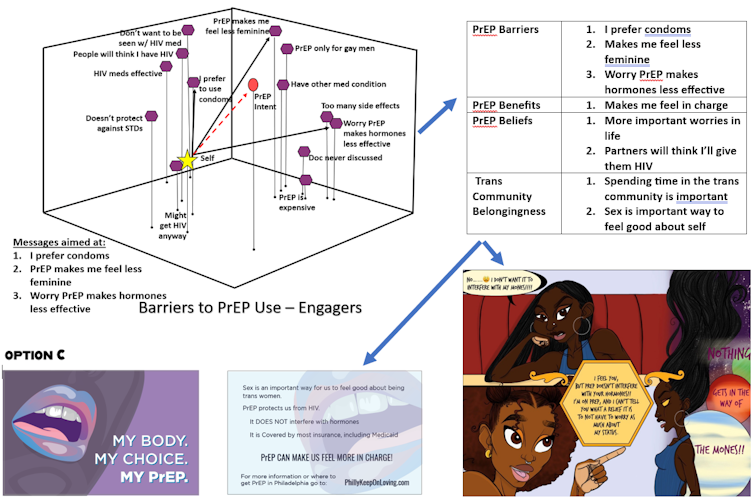

For example, I led a study in 2021 that looked at how connected transgender women living in Philadelphia and the San Francisco Bay Area felt to other members of the trans community. We wanted to see if messaging about PrEP, or pre-exposure prophylaxis, the medication used to prevent HIV infection, would need to be different depending on how connected they felt.

We found that participants who were more engaged with the trans community were not only more knowledgeable about PrEP, but they were also more likely to see the benefits of using it compared with those who were less engaged.

This indicates that strategies to reach those not as connected may need to include, for example, providing more basic information about what PrEP is and how it works.

Mathematical models and 3D maps

Another powerful marketing tool that I use is a process known as perceptual mapping and vector message modeling.

Using simple survey answers, we can mathematically model how people are thinking about a health decision and present it in a three-dimensional map.

Similar to how someone might think about the relationship between where cities or countries are in relation to each other – such as where Philadelphia is in relation to New York or Chicago – we can take answers from a survey and convert them into distances. We ask people to agree or disagree to statements about the benefits or barriers to a decision and enter their responses into a computer program to create the map.

We can then do vector message modeling, which shows how to move the group toward the desired decision.

Think back to high school physics when you may have learned about the amount of force, or pushing and pulling, needed to move one object toward another. Vector message modeling helps us figure out which beliefs to push or pull against to get the group to move toward a particular decision, and it helps us create the most persuasive messages for that group.

When we use vector modeling along with segmentation analysis, we can also compare how messaging may need to be similar or different for different groups.

For example, I used segmentation analysis and then perceptual mapping and vector message modeling to understand how medical mistrust might affect the decision to get vaccinated for COVID-19 among a group of Philadelphians who had not yet been vaccinated.

Our team then looked at perceptual maps and vector message modeling by levels of mistrust. The vectors showed that those with high levels of medical mistrust would be more likely to respond to messages that addressed concerns about the pandemic being a hoax, or the worry that minorities wouldn’t get the same treatment as others.

This allowed us to think about how to build in messages around those issues in public media campaigns or other communication strategies that encourage vaccination.

Decision-making tools

I have used these methods to create and test a number of different communication strategies to influence health decisions.

For example, I’ve developed web-based tools that have been used in hospitals and clinics in Philadelphia to encourage methadone patients with hepatitis C to receive antiviral treatment for their infection, Black cancer patients to take part in a clinical trial or to get genetic testing, and patients with low literacy and higher risk of colorectal cancer to have a colonoscopy.

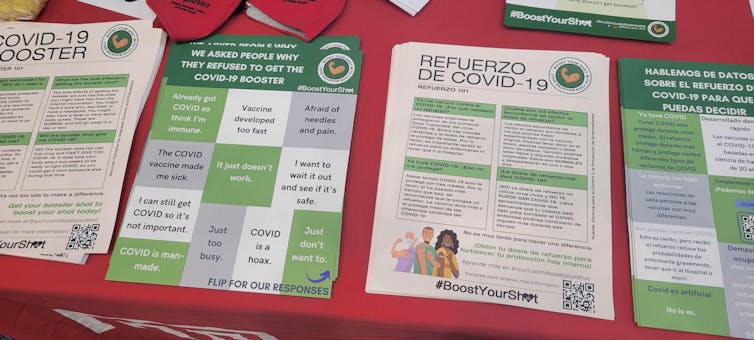

My colleagues and I have also developed posters, booklets and social media posts that encourage low-income and vaccine-hesitant Philadelphians in Kensington to get COVID-19 booster shots; educational slides for low-literacy Philadelphia adults on dirty bombs and how the radioactive weapons might be used in a terror attack; and a comic book for trans women to learn about the benefits of PrEP use.

Getting people to make better decisions about their health can be an uphill battle. We all have our reasons for not doing things that are good for us. For example, what did you eat for lunch today? Was it healthy? If not, why did you eat it?

My job is to figure out what makes people do what they do, and then help them make decisions that keep them healthy.

Read more of our stories about Philadelphia.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·