As a glaciologist who thinks about ice a lot, rewatching the movie Frozen umpteen times with my six-year-old daughter provides ample opportunity for my imagination to run wild. The movie is set in the fictional kingdom of Arendelle, which is modelled on a fjord landscape, complete with a large glacier at the head of Arenfjord. Ice unsurprisingly plays a very prominent role in the story. Yet this glacier receives very little attention.

Glaciers are receding across the world at an unprecedented rate. And on more than one occasion I have wondered how Arendelle’s glacier might have fared since the time of Frozen.

To add some scientific rigour to this thought experiment, it is useful to approximate a real geographical location. Arendelle is inspired by the fjords of western Norway, a region where most of the glaciers flow from the Jostedalsbreen ice cap, the largest ice mass in mainland Europe.

We can also approximate the date. Based on various clues, including the clothing and technology on show, it appears the events in Frozen take place one July in the mid-19th century. This means the glacier is depicted towards the end of the little ice age, a cool period lasting several centuries during which most northern hemisphere glaciers expanded to their largest size in recent history.

In the movie, the glacier plunges from a high elevation plateau into the fjord below and looks steep and crevassed at the front. This implies a healthy, advancing glacier, in a similar condition to the many outlet glaciers of Jostedalsbreen that reached their little ice age maximum positions around this time.

The short-term health of Arendelle’s glacier may have been further boosted by the unseasonal summer snowfall and cold temperatures that Elsa’s powers unleashed on the kingdom.

Real glaciers are shrinking fast

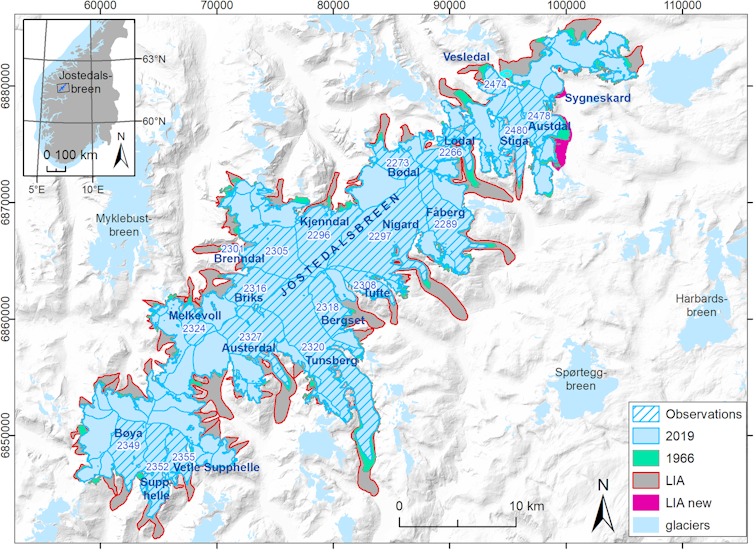

The fate of the fictional glacier since the little ice age would have been less positive, as demonstrated by the very real glaciers of Jostedalsbreen. This period has been characterised by accelerated climate warming, causing widespread glacier retreat and thinning.

Since Elsa’s time, the real glaciers it’s based on have shrunk by about a fifth. Individual glaciers have retreated several kilometres at rates of up to 20 metres per year. This makes it likely that, without any further help from Elsa, Arendelle’s glacier would have retreated onto land within decades of the time of the film.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, an increase in winter snowfall in western Norway meant most major glaciers in the region began to advance up to a few hundred metres. The Arendelle glacier might therefore have grown again for a time, although probably not enough for the glacier to re-enter the fjord. While there are other explanations, the more imaginative mind might consider the possibility that a descendent of Elsa was responsible for this period of increased snowfall.

Since the early 2000s, those same glaciers have shrunk significantly, retreating by up to 70 metres per year. That’s largely because higher air temperatures mean more ice is melting in summer. Several of Jostedalsbreen’s glaciers have retreated almost back onto the plateau, while others are disconnecting from the larger ice bodies that have been nourishing them for centuries.

What would Arendelle’s glacier look like today?

Retreat of this scale means the fictional glacier today might look something like Briksdalsbreen, now just a small tongue spilling over from the plateau ice behind. Indeed, it is quite possible that in 2025, designated by the UN as the International Year of Glaciers’ Preservation, Arendelle’s glacier would no longer have been visible from Arendelle Castle.

So, if Arendelle’s glacier were real, it would be a shadow of its 19th-century self – much like its real-life Norwegian equivalents. By 2050, approximately 200 years after the time of Frozen, the glacier would probably have retreated onto the plateau. The ice cap would also have thinned considerably and might even be in the early stages of terminal break up.

However, while this is one potential scenario for Jostedalsbreen in the 21st century, it is by no means certain. Climate scientists agree that concerted action is needed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to limit warming.

Magic helped Arendelle once. This time, it’ll take real-world action to ensure the real glaciers have a fighting chance of still being around by the time Frozen 3 is finally released.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 45,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·