The global food system is increasingly at risk from climate change, even as farmers work to adapt, according to a June 18 study in Nature.

Contrary to earlier research suggesting warming might boost food production, the new study estimates that each additional degree Celsius of global warming could reduce food availability by an average of 120 calories per person per day — about 4.4% of current daily intake.

“When global production falls, consumers are hurt because prices go up and it gets harder to access food and feed our families,” said Solomon Hsiang, professor of environmental social sciences at the Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability and a senior author of the study. “If the climate warms by 3 degrees, that’s basically like everyone on the planet giving up breakfast.” That’s a high cost for a world where more than 800 million people at times go a day or more without food because of inadequate access.

The projected losses for U.S. agriculture are especially steep. “Places in the Midwest that are really well suited for present day corn and soybean production just get hammered under a high warming future,” said lead study author Andrew Hultgren, an assistant professor of agricultural and consumer economics at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. “You do start to wonder if the Corn Belt is going to be the Corn Belt in the future.”

Hultgren and co-author Solomon Hsiang collaborated with more than a dozen researchers over eight years on the study, part of a broader effort by the Climate Impact Lab — a research consortium co-led by Hsiang, University of Chicago economist Michael Greenstone, Rutgers climate scientist Robert Kopp, and climate policy expert Trevor Houser of the Rhodium Group.

“This is basically like sending our agricultural profits overseas. We will be sending benefits to producers in Canada, Russia, China. Those are the winners, and we in the U.S. are the losers,” said Hsiang. “The longer we wait to reduce emissions, the more money we lose.”

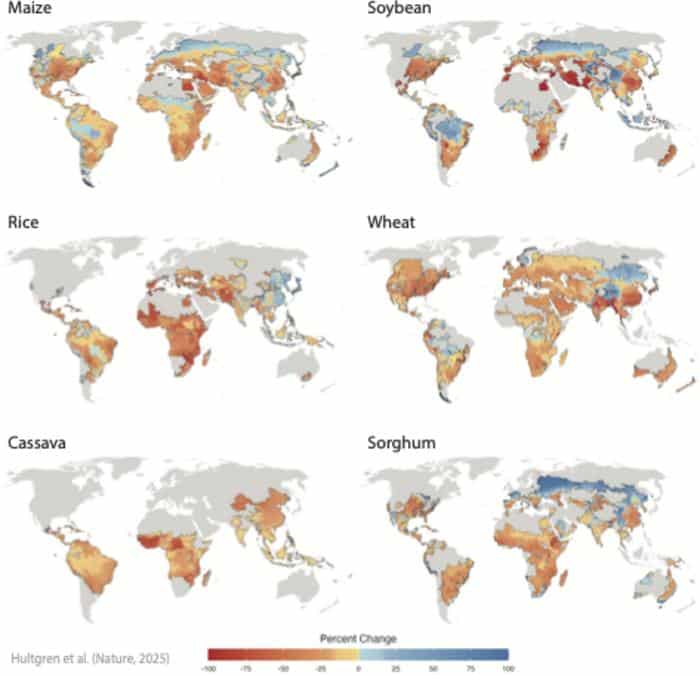

Projected end-of-century change in crop yields resulting from climate change in a scenario where emissions remain high, accounting for adaptation to climate and increasing incomes. Photo: Adapted from Hultgren et al. (Nature, 2025)

Projected end-of-century change in crop yields resulting from climate change in a scenario where emissions remain high, accounting for adaptation to climate and increasing incomes. Photo: Adapted from Hultgren et al. (Nature, 2025)Limits to Adaptation

The study analyzes data from over 12,000 regions in 55 countries, focusing on the six crops that supply two-thirds of the world’s calories: wheat, corn, rice, soybeans, barley, and cassava, according to a press release.

Unlike earlier research that assumed either “perfect” or zero adaptation, this study is the first to systematically quantify how farmers actually respond to changing conditions. In many areas, that means switching crop varieties, adjusting planting and harvest dates, or changing fertilizer practices.

These efforts help — but only to a point. The researchers estimate that such adaptations could offset about one-third of climate-related crop losses by 2100 if emissions continue on their current path, leaving the majority of the damage in place.

“Any level of warming, even when accounting for adaptation, results in global output losses from agriculture,” said Hultgren.

Higher Emissions Mean Greater Losses

With global temperatures already about 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, many farmers are grappling with longer dry spells, heat waves at the wrong times, and increasingly erratic weather — all of which hurt yields, even when fertilizer and irrigation are improved.

The study modeled future crop yields under various warming and adaptation scenarios. By 2100, global yields are projected to decline by 11% if emissions fall rapidly to net zero. If emissions continue unchecked, that drop could reach 24%.

In the nearer term, the outlook is grim either way. By 2050, the researchers estimate that climate change alone will reduce global crop yields by 8%, regardless of future emissions cuts — since the carbon already in the atmosphere will continue to trap heat for centuries.

“If we ignore those long-run damages, we assign an economic value of zero to them, and that is clearly wrong,” Hultgren said.

New Tools to Guide Smarter Adaptation

Hsiang, Hultgren, and their colleagues are now focused on helping policymakers better allocate adaptation resources — especially in regions where farmers still lack essentials like high-quality fertilizer and reliable weather forecasts.

Partnering with the United Nations Development Program, the team is sharing their climate risk findings with governments worldwide. They’re also building a system to pinpoint the communities most vulnerable to crop losses — and where targeted support could have the greatest impact.

“We’re focusing on how to make it so that this is not actually what our future looks like, even if we can’t get our act together on the emissions side,” Hsiang said.

A favourable climate, he added, is a big part of what keeps farmland productive across generations. “Farmers know how to maintain the soil, invest in infrastructure, repair the barn,” Hsiang said. “But if you’re letting the climate depreciate, the rest of it is a waste. The land you leave to your kids will be good for something, but not for farming.”

English (US) ·

English (US) ·